When I first stepped into a geology classroom, I never expected that studying rocks, soils, and the deep history of our planet would reshape how I understand society itself. Science is often described as a body of knowledge, but I’ve come to see it as a way of thinking that helps us explore the world with curiosity, humility, and responsibility.

Geology, especially, has taught me that the Earth is alive with stories. Every fold, fault, and grain of sand carries evidence of events that shaped our landscapes long before we were born. Learning to “read” these stories is both empowering and humbling. It also makes one thing clear: scientific literacy is not optional; it is inevitable.

The Journey from Curiosity to Responsibility

During my formal education in geology, I learned how to observe rocks and terrains, how to ask the right questions, and how to trace the processes that shaped them. I learned about landslides, earthquakes, and the subtle movements of tectonic plates that can trigger catastrophic events. I also went through the constant cycle of learning, unlearning, and relearning, which humbled me.

But I also learned that scientific knowledge comes with a responsibility to share it.

What good is our education if it stays confined within classrooms, exams, and laboratory reports? Science has meaning only when it benefits people: when it helps communities prepare for hazards, understand their environment, and make informed decisions.

When Earthquakes Strike, Misconceptions Spread Faster Than Facts

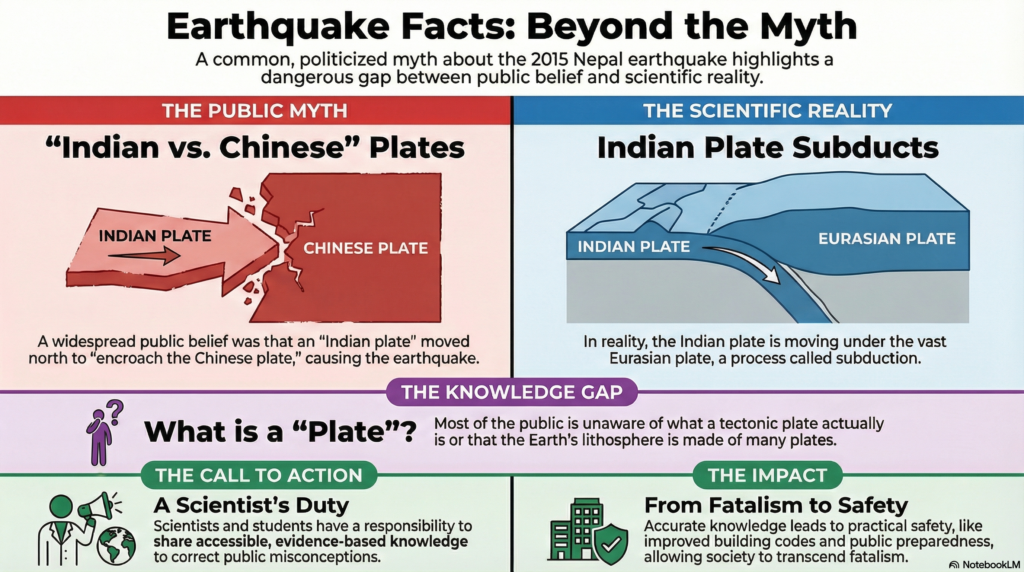

The 2015 Gorkha Earthquake (2072 B.S.) jolted Nepal awake, not just physically, but intellectually. Suddenly everyone wanted to understand why it happened. Explanations began circulating everywhere, some helpful, many not.

The most common one went something like this:

“The Indian plate is pushing against the Chinese plate, and Nepal lies between them. That’s why we had the earthquake.”

There is a hint of truth there, but only a hint.

Nepal does lie near the boundary of two major tectonic plates, but the actual process is far more complex than political labels such as “Indian” and “Chinese” suggest. The Earth’s lithosphere is divided into many plates, not just two. Their movements involve millions of years of collision, compression, faulting, and energy buildup deep beneath our feet.

Misunderstandings like these are indicators of how people perceive risk.

And that’s where scientists and science students should step in.

Science Is Not About Belief, But About Evidence

One of the most beautiful aspects of science is its honesty. It doesn’t demand belief. It asks for evidence.

When scientists encounter a new idea, the first question is never “Do I like this?” or “Does this fit my worldview?”

It is always:

“Is it true? What supports it?”

The theory of plate tectonics, now a cornerstone of geology, began as a hypothesis that many doubted. It became widely accepted only after strong evidence from seafloor mapping, paleomagnetism, and global seismic data started piling up.

That’s how science grows—by challenging itself.

And that is exactly what makes it useful in understanding the world.

Scientific Literacy Saves Lives

If there is one thing I’ve learned as a geology student, it is that science is a shared journey.

We learn from nature, from our teachers, from fellow researchers, and from the knowledge passed down by previous generations. In return, we must pass it on accurately, honestly, and accessibly.

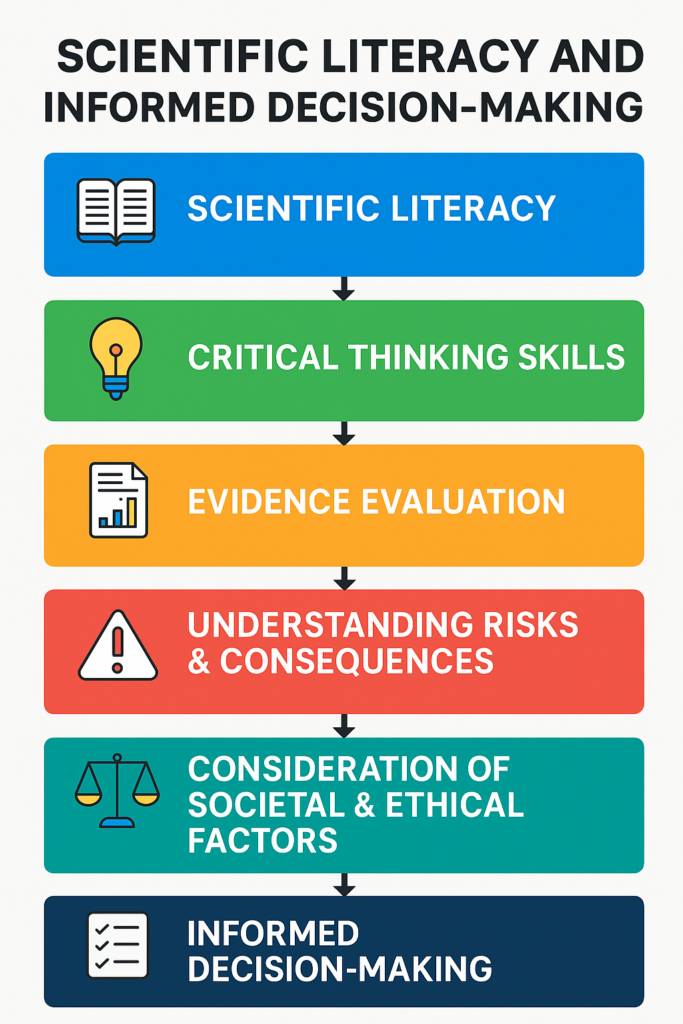

When scientific literacy improves:

- communities become safer,

- misconceptions fade, and

- society becomes more resilient.

Whether it’s understanding earthquakes or addressing climate risks, the right knowledge can quite literally save lives.

And that’s why I believe we—students, teachers, scientists, and curious citizens—must keep learning from the Earth and keep sharing what we know.

A better-informed world is always a safer world.

Leave a Reply